Plastic Pollution in the Tidal Thames

Our rivers, oceans and wildlife are being overwhelmed by plastic waste, and microplastic is entering our food and water. In London, Thames21 and the Port of London Authority (PLA) remove at least 200 tonnes of waste from the Thames each year, much of it plastic. Despite this huge problem, there is no statutory monitoring of the impact plastic is having on UK rivers.

Thames21 launched the Thames River Watch citizen science programme in 2014 to fill this gap. The programme trains Londoners to monitor plastic pollution and identify the most common plastic items, to help understand pollution sources and identify solutions.

Our 2020 report, Plastic Pollution in the Tidal Thames analyses this data, highlights the key findings and makes associated recommendations. Below is a summary.

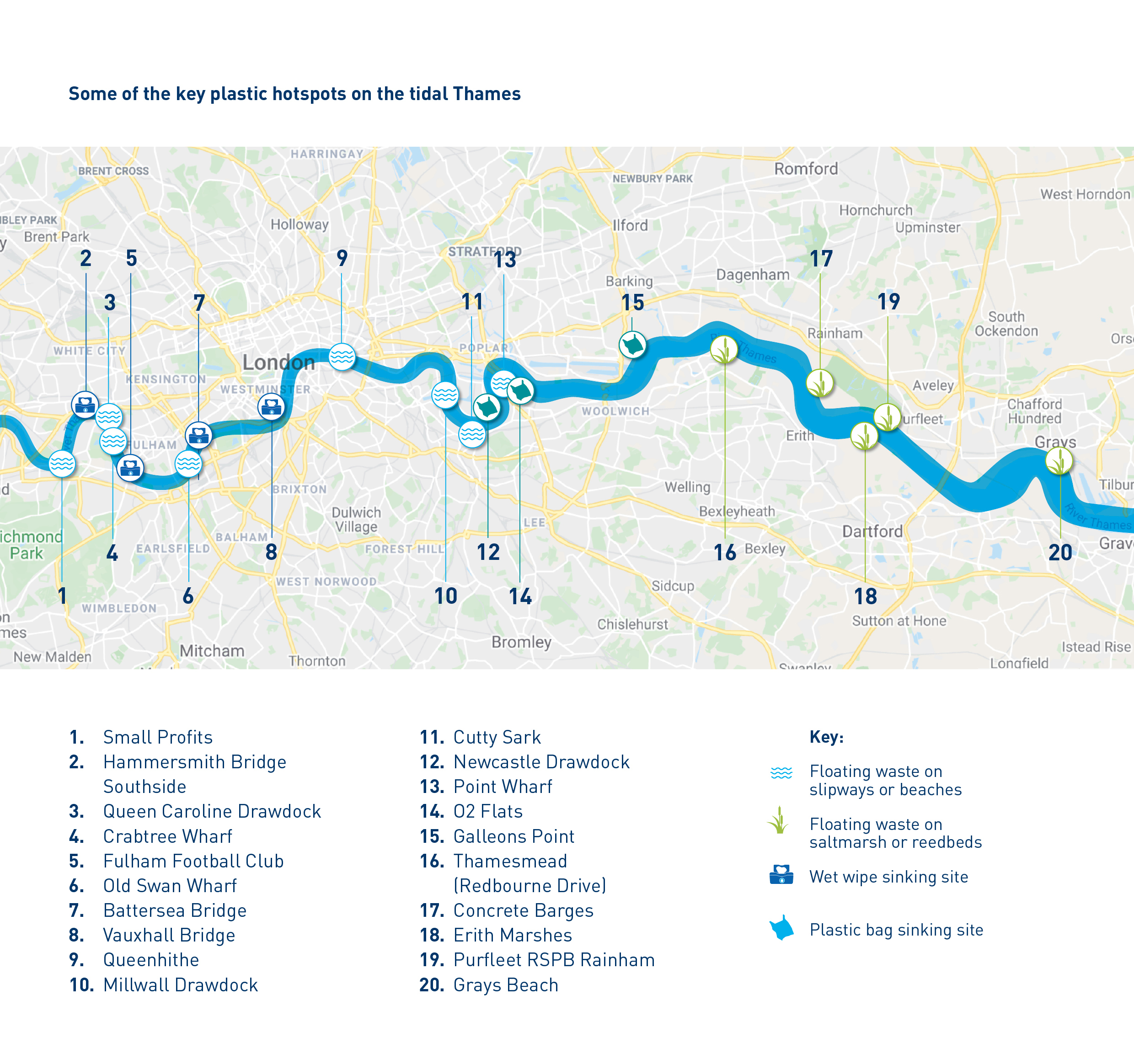

Key Plastic Hotspots

Key Findings

- Over the past 20 years there has been a significant decrease in large immobile waste items (such as tyres, metal, bicycles) due to the huge Thames21 volunteer effort to clean up the river.

- Over the same period, there has been a discernible increase in plastic consumer items and packaging in the river.

- Plastic wet wipe products are the most common item recorded on the tidal Thames foreshore in London. These products are physically changing the shape and sediment type of the foreshore across six sites.

- Single-use plastic items make up 83% of all counted items on the foreshore (excluding glass fragments)

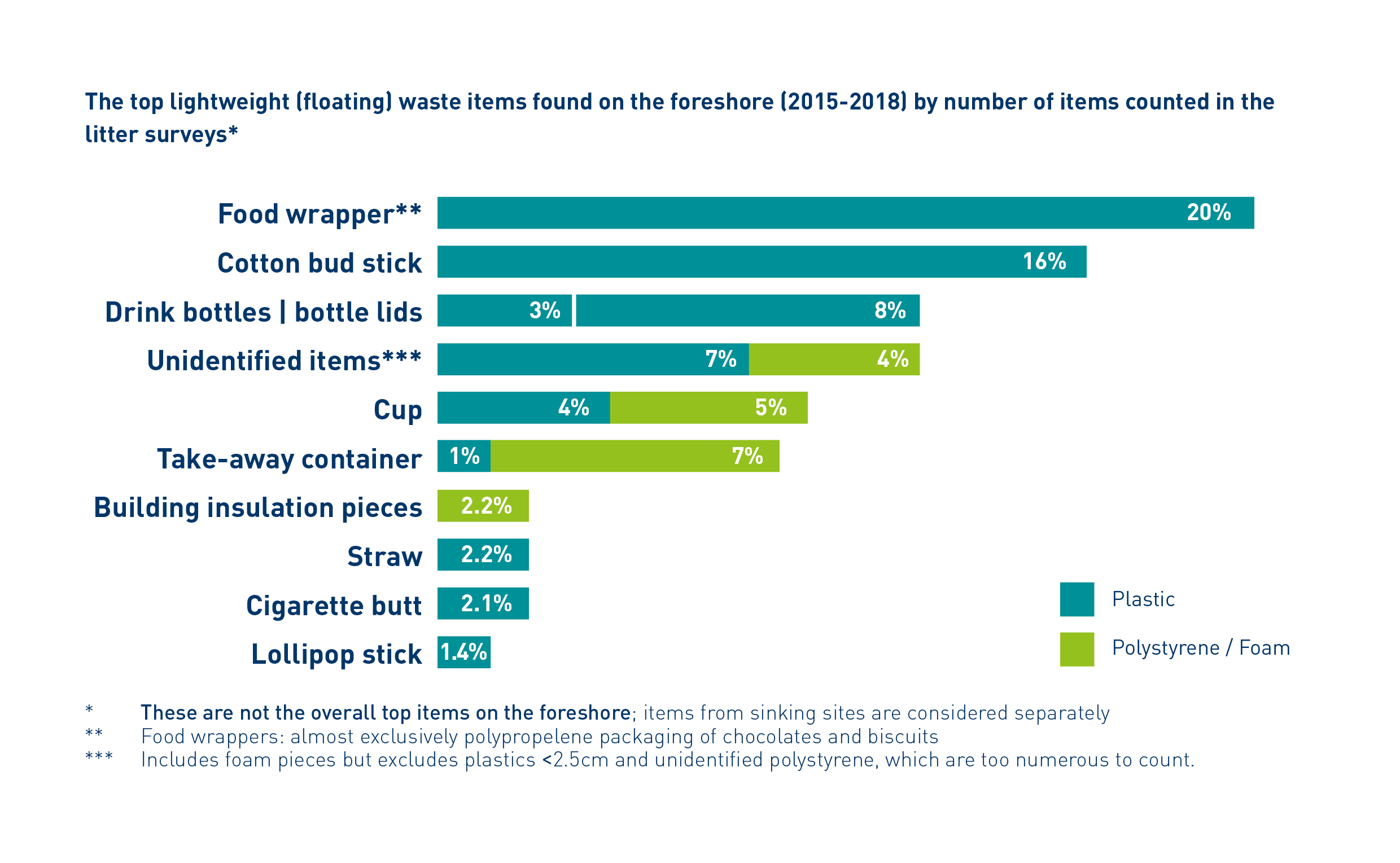

- Just five items represent nearly two-thirds of all lightweight identifiable plastic found, more than 64% of the total. These are: food wrappers, cotton bud sticks, drink bottles and their lids, cups and takeaway containers.

- A total of 97,019 drink bottles were recorded and removed between April 2016 and December 2019.

- Water bottles represent almost half of all the drink bottles found in the Thames.

- Of the total bottles recovered, 65% were found on saltmarsh and reedbed habitats outside the city, compared to 33% from slipways and beaches in London

- Of 21 sites surveyed, 20 reported the presence of microplastics at least once.

- Storms are likely depositing greater quantities of lightweight items on the saltmarsh and reedbed habitats on the Thames.

Recommendations

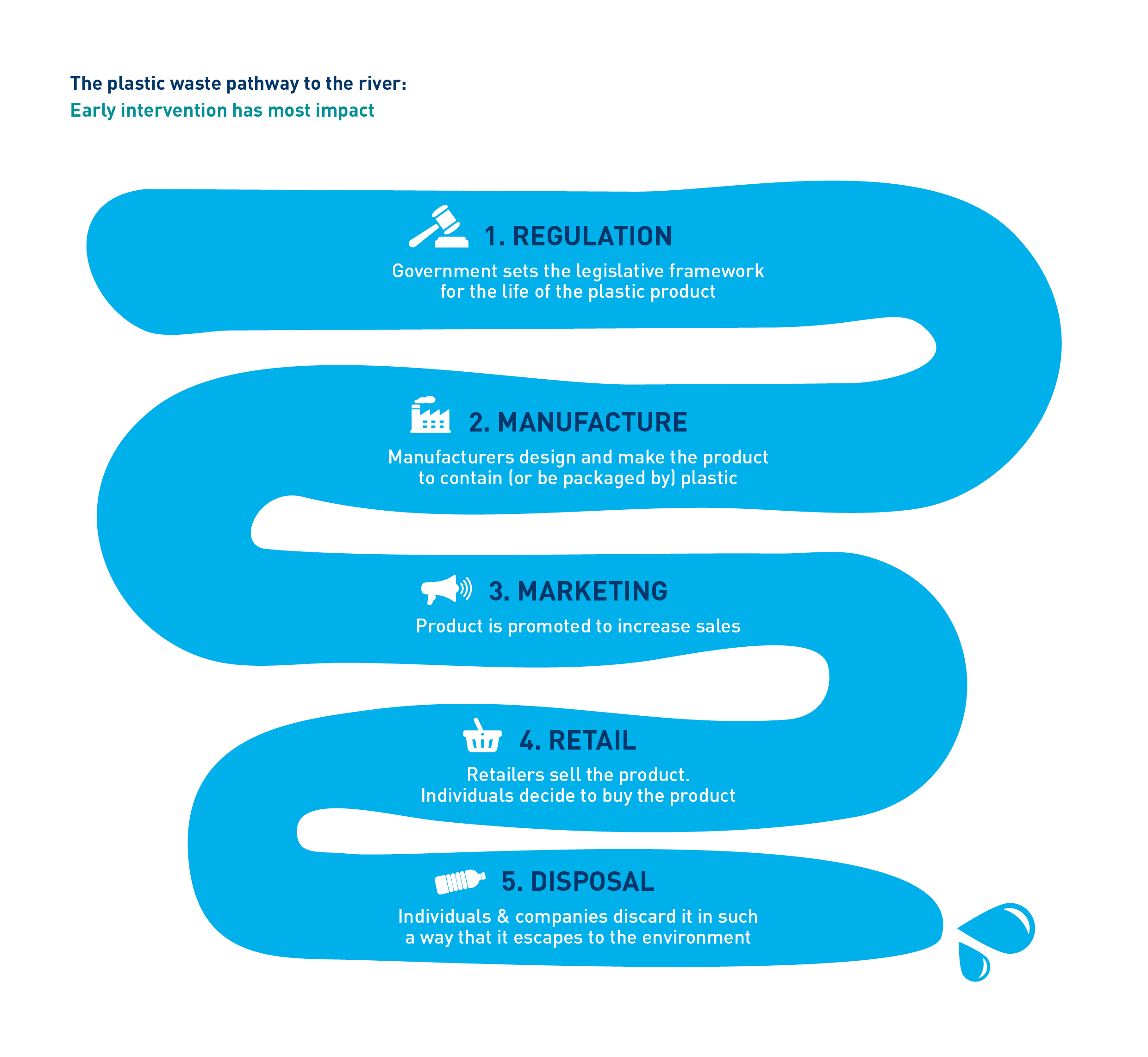

The higher up we intervene in the plastic pathway to the river, see below, the more effective that intervention will be. Greater intervention is needed from government and business if we want to turn off the tap of plastic waste.

The UK Government should:

- Establish standardised protocols for data collection from litter picking events on coasts, estuaries and rivers to provide reliable statistics on trends over time, focusing on the quantity, composition and source of litter items.

- Introduce statutory monitoring of rivers and coasts to establish the success rate of measures to reduce plastic pollution

- Set legally binding waste reduction targets to phase out non-essential waste items

- Give councils sufficient funding to collect street refuse and enforce existing laws

- Introduce strict standards on labelling to require all single-use wet wipe products containing plastic to indicate this clearly on the packaging; and to ensure that a ‘flushable’ label cannot be applied to wet wipe products that contain plastic or persistent chemicals

- Introduce an ‘all-in’ Deposit Return Scheme for bottles and cans paid for by manufacturers

- Eliminate polystyrene packaging by moving to recyclable plastic supported by a comprehensive recycling system.

Manufacturers should:

- Improve labelling voluntarily on wet wipe and sanitary products to highlight that it is damaging to flush them

- Innovate to reduce food wrapper packaging, which is particularly prone to breaking into microplastic, and make more of it recyclable.

Retailers (including bars/pubs) should:

- No longer sell wet wipe products and instead stock reusables, following the lead of companies including Holland & Barrett and Selfridges

- Switch away from single-use plastic cups to reusable ones following the example of Putney Business Improvement District

- Join the #OneLess campaign to help London become single-use plastic water bottle free.

NGOs and agencies should develop campaigns to:

- Better communicate the link between street litter, drains and our rivers to tackle the lack of awareness amongst the public about the link between drains and local rivers

- Drive consumer behaviour towards waste reduction, recycling and sustainable alternatives.

Individuals can help by:

- Not flushing any products down the toilet, even if the label claims it to be flushable: abide by the 3Ps (flush only pee, paper, poo)

- Downloading the Refill app to find their nearest refill point rather than buying water in single use plastic bottles

- Carrying cigarette butt pouches to carry butts until they can be disposed of properly

- Joining their local campaign groups, such as Thames21’s River Action Groups

- Joining Thames21’s Thames River Watch to help monitor plastic and learn how to lobby for change.