Plastic Free Mersey team engages with international wetland scientists

Last month, our Plastic Free Mersey team presented our cross-sectoral project at the 17th Society of Wetland Scientists Europe Chapter conference in Arles in southern France. More than 40 wetland scientists and practitioners from 13 countries took part in the event.

Connecting wetlands functioning and biodiversity towards nature-based solutions was the theme of the conference. The audience comprised of river-focused research groups, charities such as Thames21, and other organisations working at catchment level to better understand and conserve aquatic ecosystems.

Thames21’s Luca Marazzi and Bea Asquith presented preliminary results on our citizen science work in the Mersey catchment (see Storymap) and learnt about many exciting projects. These included projects which focused on how various species of aquatic and terrestrial plants and animals tell us about the state of our global wetlands.

Wetlands include rivers as they are defined by the Ramsar Convention for their protection “areas of marsh, fen, peatland or water, whether natural or artificial, permanent or temporary, with water that is static or flowing, fresh, brackish or salt, including areas of marine water the depth of which at low tide does not exceed six metres”.

The event was held at the fantastic LUMA foundation venue, where contemporary artistic creation is led by young professionals in the sectors of visual arts, photography, publishing, documentary films, and multimedia. All presentations were fully packed.

On day two, the Thames21 team were fortunate to participate in an unforgettable all-day field excursion in the iconic Camargue – the largest wetland in France, and the second largest delta in the Mediterranean region. Here, human history and natural history create a complex landscape in constant transformation. It is a paradise for birds and birdwatchers alike.

National breeding species include the Greater Flamingo, Glossy Ibis, and Eurasian Bittern. Wintering birds include Mallards, Red-crested Pochards, and Greater Spotted Eagles. Other birds stop by during their migration, such as Pied Avocet, Curlew Sandpiper, and Black Tern.

The inspiring surroundings of Arles and the Camargue created a great atmosphere for sharing and learning from colleagues with different professional and personal backgrounds. It also provided food for thought for the Thames21’s team to continue doing our great work to reduce plastic pollution and restore rivers and wetlands in the UK and beyond!

The Rhône River and its Delta

The Rhône basin covers 98,000 km2 and 16 million people living along its course. The Rhône travels a total of 814km from its source in the meltwater of the Rhône Glacier (Swiss Alps) through the major cities of Geneva and Lyon, ultimately reaching the Mediterranean Sea at the Camargue Delta (after splitting into two branches in Arles). With so many people living in such close proximity to the river, the pressures of urbanisation and agriculture put a strain on the river’s water quality and health.

For example, 19 hydroelectric power plants and 120 reservoirs built along the river’s length have altered the shape and course of the river, with 80% of the river’s course being artificialized. Urbanisation and conversion to agricultural land along the riverbanks and in the surrounding landscape causes large sewerage, nutrients, and litter loads, while also increasing flood risk and reducing the biodiversity of the river’s ecosystem. While new ecosystems can be created by removing hydroelectric dams through civil engineering works (as achieved on the Selune River in Vezins, Normandy), dams cannot be easily removed in the highly built-up areas along the Rhône.

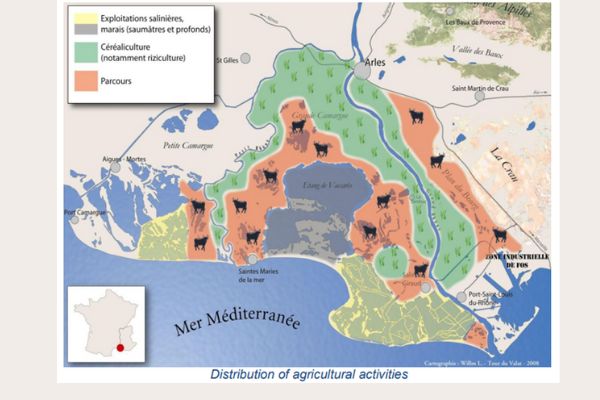

Towards the mouth of the river, the polluting inputs from the length of the river are carried through the Camargue delta and into the Mediterranean Sea. The Camargue itself is often split into three “belts”, with varying levels of management and exploitation, as shown in the map below.

Key Messages

Most of the conference’s attendees work on local wetlands or other aquatic systems in their country / region. Wetlands are key ecosystems for tackling climate change and declining biodiversity, and they contribute to reaching 6 out of the 17 UN Sustainable Development Goals: Good Health and Well-Being; Clean Water and Sanitation; Sustainable Cities and Communities; Climate Action; Life Below Water; Life on Land.

Unfortunately, the size and health of natural wetlands in the Mediterranean has been declining in the last several decades. LiDAR mapping has shown that the main driver of wetland loss in France is agricultural intensification, something that is ultimately driven by the prioritisation of economic growth over sustainability goals. This trend is rather common in richest countries, although the concern is now on emerging economies where more wetlands are left and population growth and consumption/ lifestyle improvements are driving ecosystem degradation to support livelihoods. Although the creation of man-made wetlands can offset some of the wetland loss, these cannot directly replace natural wetlands in every aspect, and may take a long time for a mature wetland to form.

Several speakers argued that we need to catalyse a paradigm shift in how people perceive and interact with nature. Many indigenous communities and people hold a deep understanding of their local natural environments and play an active role in their conservation. Indigenous knowledge is incredibly valuable, which together with more technical or scientific knowledge, will likely hold the key to successful conservation and restoration projects. Some also argued that a key step towards initiating this paradigm shift is in recognising the legal rights of wetlands and other natural environments, as in the case of the Whanganui River in New Zealand, which was granted the same legal rights as a person in order to recognise its spiritual connection with the Whanganui tribes. A group of wetland scientists, a climate scientist and attorneys led by US-based ecologist Gillian Davies are operationalising the Universal Declaration for the Rights of Wetlands to help reduce the destruction of wetlands by “calling for wetlands to be given legal rights, similar to how humans have rights”, building on many Indigenous peoples’ knowledge. A fascinating, yet very challenging endeavour considering the current and predicted trends in terms of climate change and biodiversity loss, which may be particularly severe for aquatic ecosystems, and ongoing focus on economic growth.