23 thousand wet wipes discovered on stretch of Thames river bank

Other plastic waste found included menstrual products and microplastic glitter

A record 23,000 wet wipes were counted and removed from one stretch of the Thames foreshore in just two hours last month.

473 bin bags of wet wipes were removed from the foreshore in Barnes, West London on Saturday 23 March by 160 Thames21 volunteers. They were there as part of a mass citizen science event to monitor the impact of plastic on the capital’s river. Many wet wipes, even those marketed as flushable, contain plastic fibres and therefore do not break down.

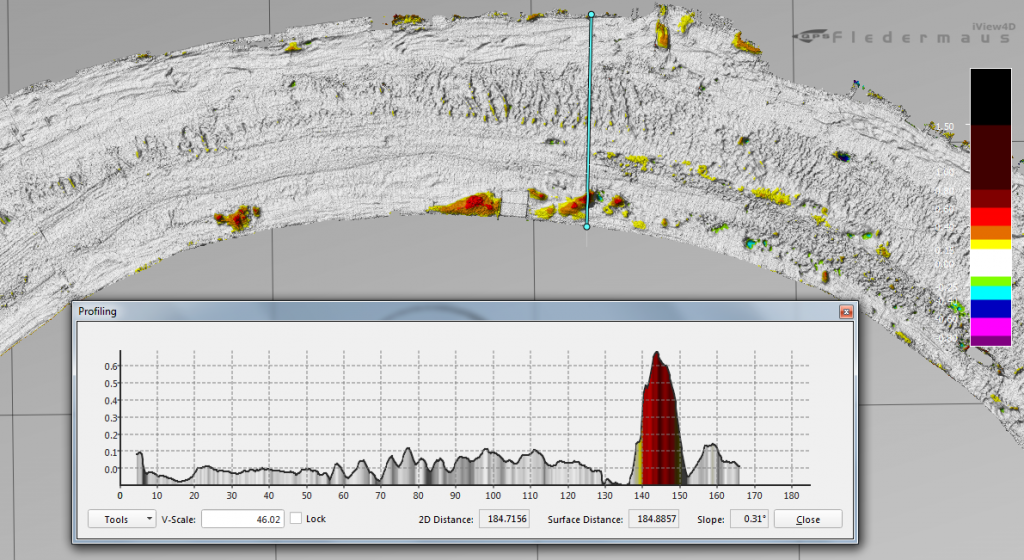

Latest data shows that the so-called ‘Thames Great Wet Wipe Reef’ is growing. Bathymetric surveys, published for the first time, reveal that one of the largest mounds, in front of St Paul’s school in Barnes, has grown by 0.7m in the past few years, and is now 50m wide, 17m long and stands at more than 1m high.

The foreshore at Barnes contains nine large mounds, which look natural, but are formed from a thick plastic wet wipe mesh mixed up with mud from the river. Thames21 volunteers were at the site to measure the density of the wet wipes on the surface of the mounds in order to chart changes over time. The average density was a worrying 201 wet wipes per square metre. Four other similar sites exist along the Thames riverbank in London.

‘The growing wet wipe market is damaging our capital’s river, turning stretches of it into a Frankenstein foreshore, part plastic part natural,’ said Alice Hall, coordinator of Thames21’s award-winning Thames River Watch citizen science monitoring programme, which organised the event. ‘Our rivers are becoming plastic rubbish dumps: millions of wet wipes, which often contain plastic, being flushed down loos and then discharged into our rivers when the sewers can’t cope. We’ve seen the mounds growing very fast over the past few years.’

Academics from Royal Holloway University volunteered at the event, taking samples for research, as they are concerned about the potential negative impact the plastic is having on Thames wildlife.

‘Three things need to happen,’ said Alice Hall. ‘We all need to Bin Don’t Flush, no matter what it says on the packet; politicians need to ban inaccurate wet wipe labelling; and we can all start choosing reusable alternatives where possible. Reusable wet wipes for make up removal and baby cleaning already exist. These, along with regular cleaning cloths, flannels and handkerchiefs, will save you money as well as save the planet.’

Alongside wet wipes and menstrual products, microplastic in the form of glitter was also found on the foreshore.

Allison Ogden-Newton, Chief Executive of Keep Britain Tidy was at the event as part of the launch of the Great British Spring Clean, a month long series of clean-ups across the UK. She said, ‘Our latest research shows that far too many of us continue to flush wet wipes and other sanitary items down the toilet and worryingly these habits are most prevalent amongst 18 to 24 year olds. Manufacturers need to step up and drive home the message with customers that these items should go in the bathroom bin and not down the toilet where they pollute our rivers and harm our wildlife.’

In the absence of statutory monitoring, Thames River Watch is the only long term programme monitoring the impact of plastic on the river.

The bathymetric image was produced by engineers at Tideway, which is currently building a new tunnel to help London’s sewage system cope with increased demand. John Sage, Corporate Responsibility Manager at Tideway, said: ‘We undertake bathymetric surveys of the River Thames every year that have shown a near 0.7m increase in the size of the wet wipe mound at Hammersmith over the past four years. This is simply unacceptable in a global city like London. Tideway’s new super sewer will help to clean up the River Thames from sewage pollution but we all have a party to play in protecting the River Thames, including putting wet wipes in the bin instead of flushing. By supporting Thames River Watch, we hope we can continue raising awareness of the environmental dangers the river faces.’

Caroline Russell, head of the GLA Enviroment Committee, was also at the mass citizen science event. She said: ‘These wet wipes, alongside menstrual products, are everywhere on this foreshore. They shouldn’t be in our sewage system. They are a main culprit in the infamous fatbergs in the capital’s pipes and tunnels. If we all Bin, Don’t Flush that will help bring this unsightly scourge to an end.’